The First Principles of Psychology – Overview

Page-ID: 23. Version 1.0.2. Last updated: 22 Nov 2023

Here is a draft for the first principles of psychology, or as we may also call it: a unified theory of psychology. The draft has not yet been reviewed by the global community, and so it is possible that it is inaccurate to some degree. The current version of the unified theory is 1.0.1.

The task of establishing the first principles of psychology is called Project One. As the project progresses articles will be added that explain the first principles of psychology in more detail and show the research that supports the conclusions. As people review the content it may also be revised. At the moment, there is only a short summary for most of the first principles, as can be seen below. For people who don’t have a rich understanding of psychology already, the summary will probably appear too abstract to understand. But as more separate articles are added, hopefully this will change.

The Mind-Brain Principle

Article: The Mind-Brain Principle

Summary:

The mind

The mind consists of conscious experience, physical and mental behaviors that it can perform, memories that it has, and other unconscious things that affect the mind’s ability to function. The mind is the perspective from the conscious being (the consciousness) itself.

The brain

The brain consists of three parts called the cerebrum, the cerebellum and the brainstem. The cerebrum consists of two hemispheres: the right and the left. The brain is made up of neurons that are connected to each other. When a neuron is stimulated, it sends an electric current throughout the neuron, and activates neurons that it is connected with. The brain receives signals from the body and sends signals to the body via the nervous system.

The mind-brain principle

The mind-brain principle states that

The mind and the brain are just different perspectives, or properties, of the same thing.

When we talk about the brain we are looking at events or phenomena as seen from the outside, which appears as physical matter and activity, specifically neurons and related biological structures. When we talk about the mind we are talking about the same events or phenomena as seen from the inside, which appear as experiences, or as things that affect experiences indirectly, like memories.

The sciences of the mind and the brain

Psychology is the study of the mind.

Neurobiology is the study of the nervous system (including the brain).

(Cognitive) neuroscience is the study of how the mind and brain relate to each other.

Sometimes, however, the term “psychology” is used as a broader term to include both the study of the mind and the brain.

When establishing the first principles of psychology, it is thus possible to limit the theory to just the study of the mind. One advantage of this is that we know a lot more about the mind than we do about the brain, and so theories of how the brain works are a lot less certain. But it can be useful to at least include the basic aspects of the brain in a unified theory of psychology, to make the connection between the mind and the brain clearer.

An analogy: The computer

The brain is like the hardware, in other words, the physical computer consisting of physical transistors connected to each other. While the mind is like the software, in other words, the programs that run on the computer.

The Entities of Psychology: Stimulus, Response and Relation

Article: The Entities of Psychology: Stimulus, Response and Relation

Summary:

The “entities of psychology” principle

Any psychological phenomenon is either a stimulus, response, a relation, or a combination of these. There is nothing else.

Stimulus

A stimulus is anything that is experienced as a coherent phenomenon. We can describe this in more loose terms as anything that is experienced as a “thing” or “event” or some kind of “unit”. For example, we experience a tree as a “thing” or coherent phenomenon, but we do not experience the combination of a cat, the movie Titanic, the sound of a fox and the eiffel tower as a “thing” or coherent phenomenon, instead, these things are experienced as four separate stimuli.

An external stimulus is a stimulus that exists outside the mind, out there in the world. In other words, the stimulus is external to the mind. For example, a tree, a song, a cat.

An internal stimulus is a stimulus that exists only inside the mind. In other words, the stimulus is internal to the mind. For example, a memory, a dream, a feeling.

Each internal stimulus can be viewed on two different levels:

The content level: What the conscious experience is about

The meta level: What the conscious experience is itself

Direct experience: When we experience an external or internal stimulus directly, for example when we perceive an external stimulus (like a tree or song) that is present in that moment, or experience an internal stimulus (like a feeling or mental image) that is present in that moment.

Indirect experience: When we experience an external or internal stimulus indirectly, for example when we remember something that we experienced before or when we are told about something that someone else has experienced.

A response is any psychological event that is caused by one or several stimuli. For example, when we feel the taste of something sweet we start to salivate, when our eyes feel dry we blink, when we hear a song that we like we feel happy. There are different types of responses. The response may be a behavior (e.g. blinking, grabbing something with the hand), a physiological response (e.g. release of hormones, increasing heartbeat), learning (i.e. forming new relations between stimuli and responses), an emotion (e.g. fear, happiness), a memory (e.g. remembering the smell of roses, a song we heard a few years ago), a prediction (e.g. expecting our the next step of the stairs to be as high as the previous step). The response can be to activate something (e.g. cause a behavior), or to inhibit something (e.g. stop a behavior).

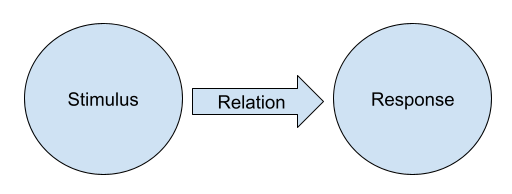

A relation is the connection between stimuli and responses that specify which responses will be triggered when one or several particular stimuli occur. When a particular stimulus causes a particular response to occur, then we can only explain this by expressing that there is a relation between the two. When one stimulus causes three responses to occur, then the stimulus has three different relations, each connected to a different response.

Figure 1 – Stimulus, relation, response

It may also be useful to define the term “context”. In relation to a specific stimulus that is in focus in one moment, all the other stimuli that are present in that moment make up the context for that stimulus. To clarify which stimuli we are talking about in one situation, we can say “context stimuli” or “contextual stimuli” for the stimuli that make up the context, and “focal stimulus” for the stimulus in focus.

The fundamental law of psychology and related principles

(Article to be added)

Summary:

All psychological events occur via the following mechanism:

- A set of stimuli occur.

- The stimuli trigger the responses which they are connected with via relations.

- If two or more stimuli have responses that are in conflict with each other, the strongest response wins

For these reasons, the basic unit for understanding psychological events is often the stimulus-response relation, which looks at how stimuli and responses are connected.

From these principles we can conclude the following:

The stimulus occurrence principle

The only ways for a stimulus to occur is either as a result of something activating our senses from outside the mind, or as a response to something inside the mind, or as a result of a combination of both.

The response occurrence principle

The only way for a response to occur is if it is triggered by a stimulus that has a relation to that response.

The response as a stimulus principle

Since a stimulus is anything that can be experienced, and there are responses that we can experience, this means that the response to a stimulus may itself be a stimulus. For example, a song (stimulus) triggers the feeling of happiness (response), this feeling is thus a stimulus in its own right. And because it is a stimulus it may in itself trigger another response.

The response awareness principle

The only way for us to experience a response is via the stimuli that the response creates. If a response does not involve the occurrence of any stimuli, we can not be aware of this response directly, only indirectly by the consequences it involves.

The relation formation principle

A new relation between a stimulus and a response can only occur as the result of a response, or as an effect of biological maturation.

The Entities of Neuroscience

(Article to be added)

Summary:

The “entities of neuroscience” principle

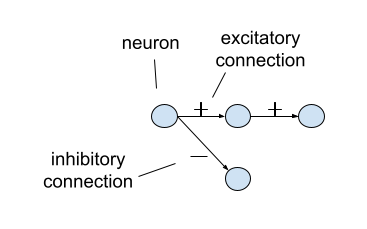

The smallest meaningful entity of neuroscience is the neuron and the connections it has to other neurons.

The connections are either excitatory (increases activity in neurons) or inhibitory (decreases activity in neurons).

The neurons of course consist of a number of different atoms and molecules, and they only function thanks to the larger biological structure they are part of like blood capillaries and glial cells, etc. So in order to understand how neurons work, and how different physical or biological events can influence neuronal activity, we need to have an understanding of that broader biological and physical science. But for the purposes of understanding what brain activity corresponds to psychological events, the level of neurons is sufficient.

Figure 2 – Neurons and connections

The fundamental law of neuroscience

All neurological events occur via the following mechanism:

- A set of neurons are activated

- The activation of these neurons triggers an increased activation of all the neurons that they have an excitatory connection with, and a decreased activation of all the neurons that they have an inhibitory connection with

- If two or more neurons have conflicting activity, i.e. one neuron triggers increased activation of another neuron, and one neuron triggers decreased activation of another neuron, the resulting activation of that neuron is the sum of the total activation

- Neurons that fire together, wire together. In other words, old connections are reinforced, and new connections are formed, between the neurons that are activated at the same time.

Connecting the mind and the brain

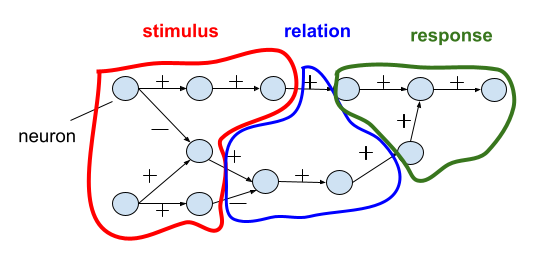

A stimulus can correspond to either the activation of a single neuron, or a set of “synchronized” neurons.

A relation can correspond to either one or several connections.

A response can correspond to either the activation of a single neuron, or a set of “synchronized” neurons, or to the formation of one or more connections.

This can be illustrated by the following example:

Figure 3 – Stimulus, relation, response and neurons

An internal and an external stimulus may correspond to the same neural activity (e.g. seeing a cat and imagining a cat). The difference lies in that when the stimulus is external, the neural activity is caused by something outside the brain, while when the stimulus is internal, the neural activity is caused by a stimulus in the brain.

Types of stimulus-response relations

(Article to be added)

Summary:

Innate or learnt stimulus-response relations

Stimulus-response relations are either innate or learnt. Innate stimulus-response relations (ISRRs) are already present from birth, or appear as a result of biological processes like hormonal changes during puberty. Learnt stimulus-response relations (LSRRs) appear as a result of the experiences of the person that gives rise to new relations between stimuli and responses.

Innate stimulus-response relation therefore consists of a pre-programmed relation between a stimulus and a response, such that the stimulus will trigger the response, even if the organism has had no prior experience from which this relation was learnt.

When a stimulus occurs there are therefore three possibilities:

The stimulus has an innate response that subsequently is triggered:

Stimulus with innate response (SIR) -> Innate response (IR)

The stimulus has a learnt response that subsequently is triggered:

Stimulus with learnt response (SLR) -> Learnt response (LR)

The stimulus has neither an innate or a learnt response:

Stimulus with no response (SNR) -> No response

There are two types of innate stimulus-response relations:

External ISRRs and internal ISRRs.

An external ISRR is the relation between an external stimulus and the mind, in other words, it consists of the physical transmission from something outside the mind to the senses, which are subsequently stimulated. For example, a visual stimulus emits light that travels through the air and stimulates the receptors in the eyes. Since this relation is not really inside the mind, we may say that the relation is “external”. Since these relations connect the mind to the world we could also call these relations (innate) “world-mind relations”.

An internal ISRR is the relation between a stimulus and a response within the mind. For example, the experience of sudden loud noise automatically triggers a fear reaction. In this case, the relation is inside the mind, and thus we may say that the relation is “internal”. We could also call these relations (innate) “mind-mind relations”.

Connecting the mind and the brain

An innate stimulus-response relation corresponds to one or several neurons that have an innate connection, or several connections, to one or several neurons.

A learnt stimulus-response relation corresponds to one or several neurons that have formed one or several connections to one or several neurons as a result of learning.

General properties of stimuli, responses and relations

(Article to be added)

Summary:

Stimulus and stimulus elements

A stimulus is something that is experienced as one “thing” or unit. Since a stimulus usually consists of many parts (and not just a single “dot” or frequency, etc), these parts are not technically stimuli in that situation, but rather “stimulus elements”. For example, in a situation where the stimulus is the whole house, the parts like walls, windows, doors, are stimulus elements of this stimulus.

Active vs inactive stimulus, relation or response

A stimulus is active during that moment that it is experienced. A relation is active during that moment when it triggers a response. A response is active during that moment when it occurs. But these may also exist in an inactive form. The stimulus-response relations do not cease to exist just because they are not currently active. Existing in an inactive state means they may be activated again at a later point, and thus are part of the network of stimuli, relations and responses.

Several responses to one stimulus

Several responses may be in a relation to, or be triggered by, one and the same stimulus, at the same time.

stimulus -> response 1 + response 2 + response 3

Several stimuli to one response

Several stimuli may have to be present simultaneously to trigger a certain response:

stimulus 1 + stimulus 2 + stimulus 3 -> response

Magnitude of stimuli and responses

Stimuli may differ in magnitude, and so may responses. For example, a dim light is a stimulus with small magnitude, while a bright light is a stimulus with large magnitude. Similarly for responses, a weak learning effect is a response with small magnitude, while a strong learning effect is a response with large magnitude.

The law of proportionality

The magnitude of a response is proportional to the magnitude of the stimulus. Given the same stimulus-response relation, a weak stimulus will trigger a weak response, compared to if the stimulus is stronger, which will trigger a stronger response.

Strength of relations

Relations may differ in strength. In other words, a stimulus may be more strongly or less strongly connected to a response. Relational strength can also be described as response sensitivity, i.e. how easily a response is triggered by a stimulus.

The law of relational strength

A stimulus that has a strong relation to a response will trigger a response of greater magnitude, compared to if it had a weaker relation to the response. In other words, a stimulus of small magnitude may still trigger a response of great magnitude if the relation is very strong (high response sensitivity). A stimulus of great magnitude may trigger a response of small magnitude if the relation is very weak (low response sensitivity).

Speed of relations

Relations may differ in speed. A stimulus may trigger a response quickly if the relation is fast, or trigger a response slowly if the relation is slow.

Connecting the mind and the brain

Magnitude

Magnitude of a stimulus or response corresponds to the level of activation of the corresponding neurons. When the neurons are strongly activated, the magnitude of the stimulus or response is bigger, and vice versa. The level of activation of a neuron corresponds to a higher frequency of the neuron’s firing.

Strength

The strength of a relation corresponds to the excitatory or inhibitory nature of the corresponding connections. Connections that are highly excitatory or inhibitory correspond to very strong relations. Connections that are only slightly excitatory or inhibitory correspond to weak relations.

Speed

The speed of a relation corresponds to the speed of the neural activity.

Innate stimulus-response relations

Given the fundamental principles of psychology that we have looked at, let us now look at the innate stimulus-response relations that organisms have. These differ from one organism to another even if there are great similarities between them. For simplicity we will look at the innate stimulus-response relations of (most) humans.

Innate World-Mind relations (External ISRRs)

(Article to be added)

Summary:

Sensory ISRRs

World-mind relations consist of all the ways that we can sense the world.

We have a number of different senses. The five most classical ones are the senses of sight, hearing, smell, taste, touch. But we have many more senses than that, for example, the senses of pressure, of hot or cold, of physical pain and physical pleasure, and senses of balance, body position, senses of hunger and of thirst. The senses are what allows us to experience the world around us, including our body.

When our senses are stimulated, sensory stimuli appear. These stimuli are experiences about whatever stimulated the sense. So, for example, when our vision (our eyes) are stimulated with light, we have experiences of that light. When our hearing (our ears) is stimulated with sound, we have experiences of that sound. In this way, sensory stimuli are special in that they always consist of a mental presentation of that “thing” in the outside world (including our body) that caused the stimulus to appear.

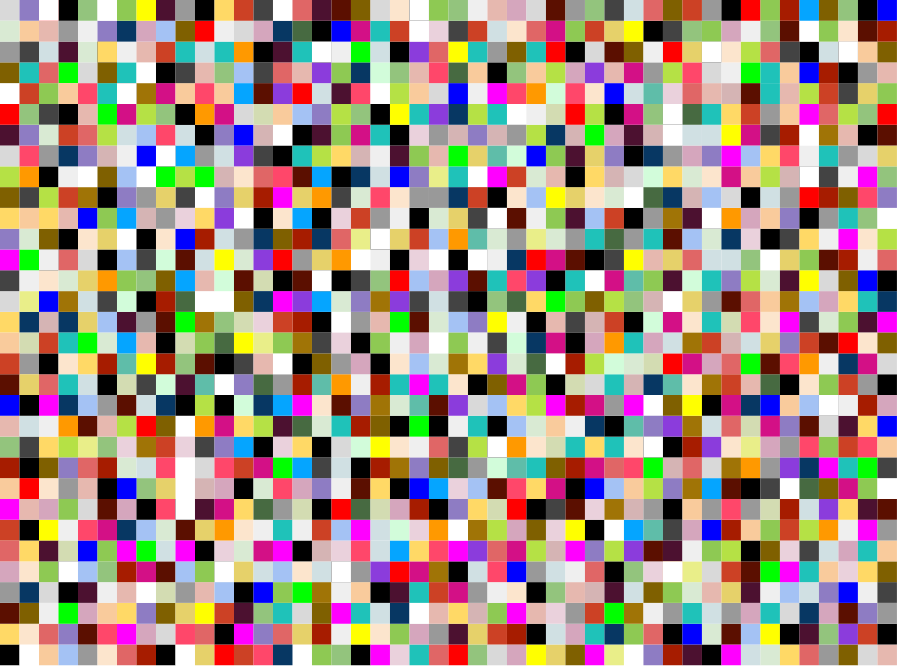

Sensory stimuli technically consist only of individual “dots”. Like the screen on a TV that consists of a number of pixels.

Figure 4 – Pixels

When the pixels combine they can display objects, landscapes, and so on, but if we look at each individual pixel it consists only of a certain color with a certain brightness, and a certain location/direction. The sensory stimuli of vision similarly consist of individual “pixels”, i.e. dots of color with different brightness and location. The sensory stimuli of sound consist of the individual frequencies from different directions. The sensory stimuli of taste consist of the individual parts of the taste, e.g. salty in one place of the tongue, and sweet in another place of the tongue.

The sensory stimuli combine to give experiences of more complete objects (e.g. a red car instead of just a collection of red dots), sounds (e.g. the sound of a bird song instead of just a collection of frequencies), etc. How these combine will be explained when we look at how the mind predicts and learns, and when we look at the innate responses that the sensory stimuli trigger in turn.

Magnitude of sensory stimuli

The magnitude of sensory stimuli depends on the level of stimulation of the sense, which in turn depends on the magnitude of the physical activity that stimulates the sense. For example, a light will appear bright when the amplitude of the light wave is great. A pressure will appear great when the physical object that presses against the sense has a great force.

Strength of relations for sensory stimuli

The strength of the relation can in this case be described in terms of how easily a sensory stimulus is triggered by the external stimulus, in other words, how sensitive the sense is.

Speed of relations for sensory stimuli

The relation may also differ in speed, such that when the relation is slow, it takes a long time before the sensory stimulus has been triggered by the external stimulus, while if the relation is fast, it takes a short time.

Innate Mind-Mind Relations (Internal ISRRs)

Perceptual ISRRs

(Article to be added)

Summary:

Depth perception

We have an ISRR that gives us an experience of depth, which is triggered by the comparison between the sensory stimuli of the different eyes.

Abstract perception

Approximate quantity

When there are a large number of stimuli (e.g. circles) relative to the space they are in, these are experienced as a large quantity compared to when there are a small number of stimuli relative to the space.

Similarly, for events spread out in time, when there are a large number of stimuli (e.g. sounds) relative to the amount of time they occur in, these are experienced as a large quantity.

Approximate duration

When stimuli occur we get an approximate sense of how long it occurs.

It is possible that there are more perceptual ISRRs, but it is difficult to know. Many of the stimulus-response relations that are often considered to be innate are probably learnt. More work needs to be done to know with more certainty.

Social ISRRs

(Article to be added)

Summary:

The world is full of other conscious beings. In order to survive in the world it is useful to be able to detect these other beings, and to understand their intentions. We have a number of innate stimulus-response relations that help us do this.

Detecting eyes:

Two “circles” with a smaller circle inside are automatically detected as two eyes.

In other words, two circles with smaller circles inside (stimuli) -> eyes of a conscious being (response)

Figure 5 – Detecting eyes

Detecting direction of gaze:

If the two smaller circles are in the center of the bigger circle, this triggers the experience of someone looking at us. If the smaller circles are down and to the right, this triggers the experience that the being is looking down to the right. And so on, for all the different directions.

Figure 6 – Detecting direction of gaze

Detecting emotion:

We also have innate stimulus-response relations that cause us to experience the emotional state of the other being. Depending on the shape of the eyes, the eyebrows and the mouth, we may experience the other person as being happy, angry, relaxed, alert, scared, etc.

Figure 7 – Detecting emotion

There are other types of stimuli that also can trigger the experience that someone has a certain emotion. Loud and rough voices trigger the experience that someone is angry. Quiet and smooth voices trigger the experience that someone is relaxed.

We further attribute the being’s emotional state as being about the thing that they are looking at. If they look at a dog and have an angry expression, this triggers the experience that the being is angry at the dog. If they look at us and have a happy expression, this triggers the experience that they are happy about something we did or are doing.

Emotional and behavioral reactions:

Further, there are innate stimulus-response relations that are triggered when we experience another being as having an emotion that cause us to experience emotion as well. For example, when we experience that someone is angry at us, a feeling of shame is triggered. When we experience that someone is happy about us, a feeling of happiness is triggered.

We also have ISRRs that trigger behavior. For example, when we see someone who is sad, we have an innate reaction to approach this person. When we see someone who is angry, we have an innate reaction to withdraw from this person.

Chaining several ISRRs together:

The different ISRRs can thus create a chain reaction, where it begins with sensory ISRRs, that then triggers the experience of sensory stimuli constituting a pair of eyes, that then triggers the experience that there is a being who is having an emotion about something, which then triggers an emotion in us.

Emotional ISRRs

(Article to be added)

Summary:

There are a number of stimuli that have an innate relation to emotional responses, i.e. that automatically trigger an emotion in us. And there are a number of different emotions that we can experience. What all emotional ISRRs have in common is that they always trigger several different types of responses at the same time:

- An experience of valence (either positive, negative, or neutral)

- A physiological reaction (for example activation of the sympathetic or parasympathetic nervous system)

- A facial expression

- An attentional attraction (“grabbing our attention”)

- A behavior (either to approach the stimulus that caused the emotional reaction, withdraw from the stimulus, or to remain still)

The experienced emotion is composed of several stimulus elements that are produced by these different responses:

The stimulus of valence, the stimuli in the body that are produced by the physiological reaction and facial expressions, the stimuli relating to having our attention drawn to something, and the stimuli produced in our body as it tries to approach or withdraw.

We can take the emotions “happy” and “anger” as an example to illustrate these emotional ISRRs.

Happiness:

Stimuli that trigger this emotion are for example, accomplishing a goal, pleasant sensory experiences (like tasting something good).

The responses produced are positive valence, activation of the sympathetic nervous system, a smile and open eyes, the attraction of our attention, and a behavior to approach the stimulus in order to have more of it.

Anger:

Stimuli that trigger this emotion are for example, unable to accomplish a goal, being hurt by someone or something.

The responses produced are negative valence, activation of the parasympathetic nervous system, clenched jaws, glaring eyes, the attraction of our attention, and a behavior to approach the stimulus in order to remove it.

List of emotional ISRRs:

Happiness, Anger, Fear, Surprise, Shame, Boredom, Love, Sexual arousal, Beauty, Ugliness, Sweet taste, Sweet smell, Disgust, Pain, Pleasant touch, Sexual pleasure, Relief, Feeling safe/cozy, and probably a few more

Other specific internal ISRRs

(Article to be added)

Summary:

There are other types of ISRRs too. But it can be difficult to place them into clearly defined categories since most stimuli with innate responses usually have more than one response (e.g. both emotional, physiological and behavioral responses). Just to list some examples:

Behavioral ISRRs

Tasting sweet food -> salivating

Puff of air in our eyes/dry eyes -> blinking

Motivating ISRRs

Feeling hungry -> increase the appeal of food

Feeling thirsty -> increase the appeal of water/liquid

Feeling tired -> increase the appeal of closing eyes and relaxing muscles

Alertness ISRRs

Darkness -> feeling sleepy

Bright light -> feeling awake/alert

Establishing that a stimulus-response relation is innate and not learnt is a difficult task. The science of psychology still has some work to do in order for us to know with more certainty whether a specific stimulus-response relation is innate or learnt. One way of figuring out the answer is to try to figure out whether it is possible to learn the relation, given what we know about learning and about other ISRRs. And if we conclude that it is not possible to learn, then we know that the relation must be innate. We will shortly look at how learning works.

General internal ISRRs

There are some innate stimulus-response relations that are of a general kind: they are activated by every single stimulus. These are the attention filtering ISRR and the prediction and learning ISRRs.

Attention filtering ISRR

(Article to be added)

Summary:

In every moment that some stimuli are present, there are always some stimuli that grab our attention more than others. As we saw earlier, emotional ISRRs cause us to turn our attention to the stimuli that evoke an emotional response in us. And as we will see later, stimuli that are unexpected grab our attention too. The attentional filter ISRR is activated every time that there is something we attend to, and has two responses:

-the magnitude of the stimuli that are the focus of attention is increased

-the magnitude of the stimuli that are not the focus of attention is decreased

Prediction and learning ISRRs

(Article to be added)

Summary:

Not all stimulus-response relations are innate. Although the innate ISRRs are the starting point for perceiving and acting in the world, most of our stimulus-response relations are learnt as we go through life. We have a set of innate stimulus-response relations that allow us to form such learnt stimulus-response relations. These are the “prediction and learning ISRRs”.

Prediction

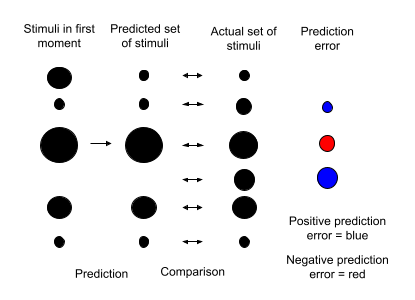

Given the stimuli that are present in one moment, the mind tries to predict what stimuli will be present in the next moment. Here is how it works:

-Each stimulus has a set of prediction responses.

-The prediction responses of a stimulus consist of those stimuli that are predicted to occur given the presence of the first stimulus.

-The prediction responses are formed via learning (as we will shortly see), and thus consist of all the learnt response relations of the stimulus.

-Making a prediction is thus the same as activating all the learnt responses of all the stimuli present in that moment, and seeing which new set of stimuli this would entail

-If the stimuli that are present have not appeared before, and therefore have no learnt responses, then nothing is predicted to occur

Prediction error

-The predicted set of stimuli are in the next moment compared to the set of stimuli that are actually present in that next moment. More specifically, it is the magnitude of each stimulus that is compared to the magnitude predicted.

-When the actual magnitude does not match the predicted magnitude, we have a prediction error. The larger the difference in magnitude, the greater the prediction error.

-The prediction error triggers a set of responses:

*attentional attraction (i.e. it causes our attention to be shifted towards the stimuli with prediction error)

*increases the magnitude of these stimuli

*triggers the emotion of “surprise”, with its physiological reactions and facial expressions

*triggers learning, i.e. the formation of learnt stimulus-response relations (see next)

-The greater the prediction error, the greater the responses.

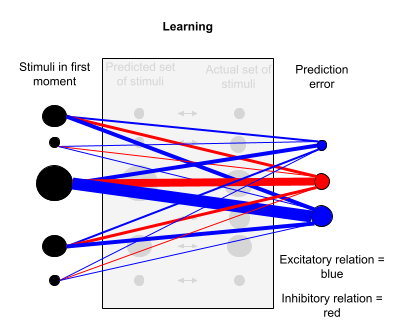

Learning

-The stimuli that were present in the first moment form new connections to the stimuli with prediction errors.

-The greater the magnitude of the different stimuli in the first moment, the more strongly they are connected to the stimuli with prediction error. In other words, a stimulus with great magnitude forms a stronger connection than a stimulus with small magnitude does.

-When the prediction error is negative (i.e. the magnitude was smaller than expected), the stimuli get an inhibitory connection to that stimulus. The more negative it was, the stronger the inhibitory connection becomes.

When the prediction error is positive (i.e. the magnitude was bigger than expected), the stimuli get an excitatory connection to that stimulus. The more positive it was, the stronger the excitatory connection becomes.

We can illustrate this process in the following way:

Figure 8 – Prediction and prediction error

Figure 9 – Prediction error and learning

The change in the learnt stimulus-response relation (i.e. the learning) of one stimulus (stimulus A) to another stimulus (stimulus B) from one moment to the next (from moment 1 to moment 2) can be described by the following equation:

The learning equation:

ΔSA→SB = g(MA/MTOT)(MB – PB-TOT)

Where

ΔSA→SB = the change in relation of stimulus A to stimulus B

g = the “general learning factor”, which is the combined effect of the general properties of an organism regarding how easily a response is triggered (how sensitive the organism is), and how quickly a response is triggered (how fast the relations are). g always has a value between 0 (i.e. no learning efficiency) and 1 (maximum learning efficiency).

MA = the magnitude of stimulus A in moment 1

MTOT = the total magnitude of all stimuli present in moment 1

MB = the magnitude of stimulus B in moment 2

PB-TOT = the total predicted magnitude of stimulus B by all the stimuli present in moment 1.

Thus, stimulus A may predict some of the magnitude, while contextual stimuli predict some of the magnitude.

The equation can be rewritten in a simpler form

The learning equation (short form):

ΔSA->SB = g𝛂ϵB

Where

𝛂 = the salience of stimulus A in moment 1. This corresponds to the magnitude of stimulus A in moment 1, divided by the total magnitude of all stimuli present in moment 1.

In other words: 𝛂 = MA/MTOT

ϵB = the prediction error for stimulus B in moment 2.This corresponds to the actual magnitude of stimulus B minus the predicted magnitude of stimulus B.

In other words: ϵB = MB – PB-TOT

This equation can thus be described in the following less symbol-heavy format:

The change in the relation Sa->Sb = (The general learning factor of the organism) * (Salience of Stimulus A)*(Prediction error of Stimulus B)

Stimulus unification principle

The stronger the learnt relation between stimuli (i.e. the more they predict each other to occur), the more they are perceived as a single unified stimulus. And thus, the connected stimuli become stimulus elements of a larger stimulus.

Putting it all together

(Article to be added)

Summary:

Network of connections

As more and more relations are learnt, the stimuli begin to form a complex network of connections between stimuli and responses. When a stimulus occurs, this activates a number of responses, and when these responses consist of stimuli, these stimuli in turn activate a number of responses, and so on. This causes the activation to spread across the network. Depending on the general sensitivity and speed of an organism, the activation may travel longer or shorter across the network when a stimulus occurs.

Stimulus properties

We can define stimulus properties as the set of:

-stimulus elements that make up the stimulus, and

-response relations that a stimulus has

Page-ID: 23

This page is version 1.0.2. It has not yet been reviewed by the global community. Do you want to help improve it? Please leave a comment in the google document for this page, or join the email group to be part of the discussion. You can always share your thoughts via email directly to mail@awiserworld.net. Read more about how you can support A Wiser World.