The Entities of Psychology: Stimulus, Response and Relation

Page-ID: 25. Version 1.0. Last updated: 22 Nov 2023

- The fundamental entities of psychology

- Stimulus

- Response

- Relation

- Context

- The Reasoning and further details

- How should we define “stimulus”?

- The question

- Why is this question important?

- Notes on strategy

- Observations

- Hypotheses (alternatives for definition of “stimulus”)

- Evaluation of hypotheses

- “A stimulus is the cause of a response” – partly correct

- “A stimulus is the object that is the cause of the response” – incorrect

- “A stimulus is the physical stimulation of receptors” – incorrect

- “A stimulus is something that is experienced” – correct but insufficient

- “A stimulus is anything we experience as a coherent phenomenon” – correct

- “A stimulus is anything that is treated by the mind as a coherent phenomenon” – insufficient

- How should we define “response”?

- How should we define “relation”?

- How should we define “stimulus”?

- Alternative terms for the concept of “stimulus”

- Alternative terms for the concept of “response”

- Alternative terms for the concept of “relation”

- Page information

- References

The fundamental entities of psychology

The first principles of psychology must both include the fundamental entities of psychology (what all psychological phenomena are made of) and the fundamental laws of psychology (that explain how psychological phenomena behave or change). In physics, the fundamental entities are particles or fields, and the fundamental laws include forces like gravity and electromagnetism, and other laws like those in quantum mechanics and special and general relativity. We need to know what the fundamental entities are in order to understand what the fundamental laws apply to. What are the fundamental entities of psychology? The answer is: stimulus, response and relation. What it means to say that these are the fundamental entities is that any psychological phenomenon is made up of these entities. They are the smallest building blocks of psychology, from which everything else can be built. We can express this in terms of the following first principle:

The “entities of psychology” principle

Any psychological phenomenon is either a stimulus, a response, a relation, or a combination of these. There is nothing else.

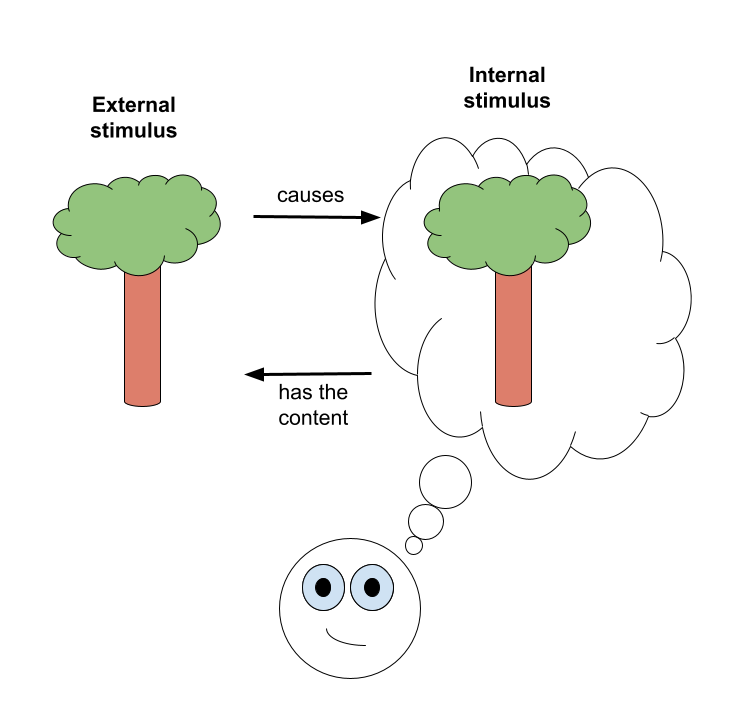

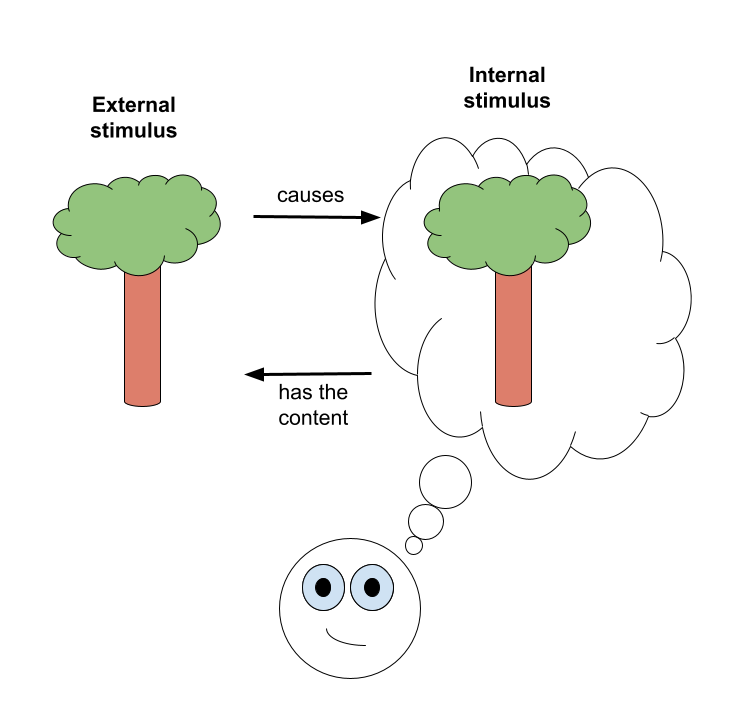

In short, a stimulus is anything that is experienced as a coherent phenomenon. A response is any psychological event that is caused by one or several stimuli. A relation is the connection between stimuli and responses that specify which responses will be triggered when one or several particular stimuli occur. The figure below illustrates how stimulus, response and relation are connected.

Figure 1 – Stimulus, relation, response

For example, the stimulus could be the smell of food. The response could be to salivate. The relation would in that case be the connection between the smell of food and the salivation. The stimulus (the smell of food) causes the response (to salivate) to occur because there is a connection in the mind between the two.

Let us now look more closely at these entities and the properties that they have.

Stimulus

A stimulus is anything that is experienced as a coherent phenomenon. We can describe this in more loose terms as anything that is experienced as a “thing” or “event” or some kind of “unit”. For example, we experience a tree as a “thing” or coherent phenomenon, but we do not experience the combination of a cat, the movie Titanic, the sound of a fox and the eiffel tower as a “thing” or coherent phenomenon, instead, these things are experienced as four separate stimuli.

Stimulus elements are the parts of a stimulus that the stimulus consists of. For example, when we see the face of a person as a single stimulus, then the eyes, ears, mouth, nose, hair, etc are the stimulus elements of that stimulus. If we focus our attention towards any of the stimulus elements they can become stimuli of their own, but in the very moment where the whole face is the stimulus, the stimulus elements are not technically stimuli on their own.

There are two broad types of stimuli:

An external stimulus is a stimulus that exists outside the mind, out there in the world. In other words, the stimulus is external to the mind. For example, a tree, a song, a cat.

An internal stimulus is a stimulus that exists only inside the mind. In other words, the stimulus is internal to the mind. For example, a memory, a dream, a feeling.

Types of causal power

External and internal stimuli have different forms of causal power. External stimuli can cause things to happen even when we have no experience of them, while internal stimuli can only cause things to happen while we experience them. For example, since an apple is an external stimulus, it can fall from a tree and land on the ground, even if no one is there to see it. And since the thought of a unicorn is an internal stimulus, it can cause a person to think of a rainbow, which is another internal stimulus, but it cannot cause a physical rainbow to appear. Thanks to this, external and internal stimuli can bring about different types of psychological responses, and differ in how they do so.

Types of psychological responses

External stimuli can only cause one type of psychological response called “sensation”, and it does so by stimulating the senses of an organism via transmission of physical energies. For example, when light enters our eyes, the light energy stimulates the millions of receptors at the back of the eye and brings about millions of consciously experienced tiny dots of different colors and intensities. When a sound wave enters our ears, the sound energy can stimulate thousands of receptors inside the ear, resulting in a conscious experience of thousands of individual frequencies. External stimuli thus only cause raw sensory data to occur. Each sensory data (for example, each dot or frequency) is an internal stimulus or stimulus element, which corresponds to a particular physical energy in a specific location. But on its own it usually doesn’t make much sense. Instead of seeing a million dots, we would prefer to see objects, landscapes, animals, movements. Instead of hearing a thousand frequencies we would prefer to hear voices, songs, sounds. This is what happens after the external stimuli have been sensed by the mind and thus the creation of internal stimuli.

Internal stimuli cause all the other types of responses aside from that of sensation. This includes responses like perception, behavior and emotion. When internal stimuli or stimulus elements have been created by external stimulation, they first set off the response of perception. Perception is the process where the individual stimulus elements of sensation are put together to more meaningful wholes. For example, when a number of black dots are placed next to each other in a line, this creates the experience of a black line, instead of just a collection of black dots. When we in a certain moment hear a number of frequencies that have a relationship with each other in the form of a harmonic series, this creates the experience of a tone with a certain timbre, instead of just a collection of frequencies.

Each internal stimulus can be viewed on two different levels:

The content level: What the conscious experience is about

The meta level: What the conscious experience is itself

For example, let’s take the experience of hearing a song. The content of this experience is the song itself. This is an external stimulus, something that exists outside the mind. But the experience of hearing a song itself is an internal stimulus, this is the meta level of the stimulus. Another example is the experience of thinking about a unicorn. The content of this experience is in this case an internal stimulus, since the unicorn only exists in our minds (if we are not talking about a drawing of a unicorn or something like this). The experience itself is also an internal stimulus, i.e. a thought. So in this case, both the content level and the meta level describe internal stimuli.

Direct experience: When we experience an external or internal stimulus directly, for example when we perceive an external stimulus (like a tree or song) that is present in that moment, or experience an internal stimulus (like a feeling or mental image) that is present in that moment.

Indirect experience: When we experience an external or internal stimulus indirectly, for example when we remember something that we experienced before or when we are told about something that someone else has experienced.

Response

A response is any psychological event that is caused by one or several stimuli. For example, when we feel the taste of something sweet we start to salivate, when our eyes feel dry we blink, when we hear a song that we like we feel happy. There are different types of responses. The response may be a behavior (e.g. blinking, grabbing something with the hand), a physiological response (e.g. release of hormones, increasing heartbeat), learning (i.e. forming new relations between stimuli and responses), an emotion (e.g. fear, happiness), a memory (e.g. remembering the smell of roses, a song we heard a few years ago), a prediction (e.g. expecting our the next step of the stairs to be as high as the previous step). The response can be to activate something (e.g. cause a behavior), or to inhibit something (e.g. stop a behavior).

A response must be observed in some way in order for us to know that it occurred. There are three ways we can observe a response:

- Direct experience by an outside observer. For example, when we see an organism move, or when we observe physiological reactions of the organism like crying or increased heart rate.

- Direct experience from the inside, by the organism itself. For example, when we observe feelings or thoughts that we have.

- Indirect experience where the response is inferred from its observable consequences. For example, we infer that a memory was created because at a later point in time we remember something.

The response to a stimulus can be to produce another stimulus. For example, when we see a wolf we have the response of being scared. The feeling of being scared is also a stimulus. So when we say that a stimulus causes another stimulus to occur, then what is really going on is that the occurrence of the second stimulus is a response to the first.

Relation

A relation is the connection between stimuli and responses that specify which responses will be triggered when one or several particular stimuli occur. When a particular stimulus causes a particular response to occur, then we can only explain this by expressing that there is a relation between the two. When one stimulus causes three responses to occur, then the stimulus has three different relations, each connected to a different response.

Context

Another concept that is useful to define, even though it is not a fundamental entity, is “context”. When a specific stimulus is in focus in one moment, all the other stimuli that are present in that moment make up the context for that stimulus. To clarify which stimuli we are talking about in one situation, we can say “context stimuli” or “contextual stimuli” for the stimuli that make up the context, and “focal stimulus” for the stimulus in focus.

The Reasoning and further details

How should we define “stimulus”?

The question

How should we define “stimulus”?

Why is this question important?

The term “stimulus” is central to psychology, and in particular in the unified theory. If we don’t have a good understanding of what a stimulus is, then the laws that are applied to stimuli will yield the wrong results. Trying to define the term “stimulus” is also part of a broader ambition to define what the fundamental entities of psychology are. In physics, for example, the fundamental entities are particles (to put it in rough terms), and the laws of physics apply to these fundamental entities. If we don’t know what the fundamental entities are in a field, then we won’t know how the laws are applied with any good accuracy. So defining the term “stimulus” correctly is therefore crucial in order to set up the field of psychology from first principles.

Notes on strategy

Establishing the first principles of a field means finding all of the fundamental entities of the field. This means that all phenomena within the field must be explained in terms of the fundamental entities. If the terms “stimulus”, “response” and “relation” are to be established as the fundamental entities of psychology, then all psychological phenomena must be able to be categorized as one of these, or a combination of them. When defining the term “stimulus” we must therefore make sure that this definition allows us to establish the full set of fundamental entities.

Observations

Behaviors occur as a response to sensory phenomena (For example, visual, auditory, taste, smell)

Responses are triggered by physical energies (for example, sound waves activate our auditory receptors, heat energy activates our heat-sensing receptors)

Stimulating a nerve with electricity can cause muscles to twitch.

A certain phenomenon that has been shown to cause a response, might not succeed in doing so every single time it occurs, but merely most of the time.

Responses can occur when an event/phenomenon is predicted to occur but does not appear. In other words, it is triggered by the surprise of the absence of stimulation. ( the response does not occur because of the activation of receptors, but rather the opposite).

The comparison (i.e. relation) between two phenomena or events can cause a response (i.e. not the activation of receptors per se, but a higher level comparison becomes a stimulus)

A response to a pattern (for example, a certain arrangement of dots, or objects) can be different from the response to when the individual parts occur on their own. This is true both of spatial patterns and temporal patterns (i.e. sequences).

When the phenomenon triggering a response is unchanging for a certain amount of time, the response eventually stops.

The greater the magnitude of a phenomenon that causes a response, the greater the magnitude of that response

We have experiences of phenomena or events around us.

There are things in the world that we can not experience directly, but merely conclude to exist via indirect observations (for example, very low frequencies and very high frequencies of light and sound)

We have experiences of phenomena or events that are merely in our minds (e.g. thoughts and feeling)

When we have certain experiences, certain responses may be caused to occur.

Even things we imagine in our mind can trigger responses.

There are certain experiences that do not cause a response to occur.

It may be that events or phenomena that are too weak or brief to be consciously experienced can trigger a response to a weak degree.

Hypotheses (alternatives for definition of “stimulus”)

There are a number of aspects of the definition of “stimulus” that need to be specified, this includes what type of phenomenon that a stimulus is, its level of granularity, whether it is something potential or actual, its degree of effectiveness, and the viewpoint from which it ought to be defined. A complete definition of stimulus must take a stance on the available hypotheses for all of these aspects.

[Regarding a stimulus’s type of phenomenon]

A stimulus is the cause of a response.

A stimulus is the object that is the cause of the response

A stimulus is the physical stimulation of the receptors of the organism, described in terms of the physical energies involved.

A stimulus is the activity of the receptors of the organism (regardless of what physical energies were involved in order for that activity to appear).

A stimulus is something that is experienced by the organism

A stimulus is anything we experience as a coherent phenomenon

A stimulus is anything that is treated by the mind as a coherent phenomenon

[Regarding a stimulus’ granularity]

A stimulus is a single cell, or “pixel”

OR

A stimulus is a pattern of cells or “pixels”

[Regarding a stimulus’ potentiality]

A stimulus is something that can cause a response/be experienced/activate receptors, etc

OR

A stimulus is something that does cause a response/ being experienced/activating receptors, etc.

[Regarding a stimulus’ effectiveness]

A stimulus is something that triggers a response

OR

A stimulus is something that merely motivates the individual to perform responses, and so the response isn’t automatically triggered

[Regarding a stimulus’s viewpoint]

A stimulus is defined from the viewpoint of the organism performing the response

OR

A stimulus is defined from the viewpoint of the outside observer

A stimulus in a given situation is something that is experienced as a more or less coherent phenomenon, i.e. as a “thing” or “unit”.

Or, in the case of subliminal perception: something would be experienced as a “thing” if it had occurred for long enough to be consciously experienced.

Evaluation of hypotheses

“A stimulus is the cause of a response” – partly correct

There are many observations where psychological responses are caused by the occurrence of some phenomenon or event. Defining “stimulus” as those phenomena or events which cause a psychological response would therefore make a lot of sense. But there are also a set of problems with this definition.

First, whenever we talk about causality, the situation is always more complex than it may initially seem. For example, if a car crashes we may try to uncover what caused the car to crash. We may discover that one of the wheels came off the car before the crash, and so we might want to say that what caused the car to crash was that the wheel came off. But the reason that the wheel came off was because it hadn’t been securely tightened, so we could equally say that what caused the car to crash was that the wheel hadn’t been securely tightened. But the reason that the wheel wasn’t securely tightened was that the car mechanic had failed to notice that the wheel was loose. So we may say that the car crashed because the mechanic had failed to notice the loose wheel. But the reason that the mechanic failed to notice that the wheel was loose was that the owner of the company had distracted the mechanic. And so on. Where do we stop? What was the “real” cause of the car crash? We could continue to go back in time until we reach the Big Bang, the birth of the universe, but it does not seem reasonable to say that the car crash was caused by the Big Bang. Similarly, we could discover that the car was traveling on a bumpy road when the wheel came off, and if the driver had chosen to drive on another road, the wheel would not have come off. So we could equally say that the car crash was caused by the bumpy road, or if we wish, by the decision of the driver to drive on the bumpy road. And once again we could then go back in time step by step to find the ultimate cause behind the car crash. We could also point out things like if there hadn’t been a tree where the car was driving, the crash wouldn’t have occurred either, so we could argue that it was the tree that caused the crash to occur. We could go on forever.

So trying to define “stimulus” as a cause isn’t really enough to tell us what that “thing” was that caused the response to occur. When we blink, this response can be said to be caused by the air that caused the eye to become dry, or we could define the cause as the “dryness” of the eye, or we could define it as the stimulation of the receptors in the eye that sensed the dryness or the air, or we could define it as the neurons that were activated by the stimulation of the receptors. Which of these alternatives is the correct stimulus if we choose to define “stimulus” as the cause of the response? In similarity with the example of the car, we could expand the options forever, perhaps the stimulus is the person’s decision to stare at the scenery, which resulted in the eye becoming dry. Or it is the movements of the wind across the globe that are the stimulus, since this is what caused the air to hit the person’s eye. And so on.

Merely defining “stimulus” as that phenomenon that causes a psychological response isn’t good enough. The definition is too general for us to be able to tell which phenomenon is the stimulus in a specific situation. There are too many things that could be said to be the cause of a response. Our definition isn’t precise enough to tell us which is the correct choice. Being able to cause a response may still be a central feature of stimuli, but it isn’t sufficient as the definition of “stimulus”. Perhaps we could just add some more details to this definition to solve this problem? There are some suggestions along these lines that we can take a closer look at.

“A stimulus is the object that is the cause of the response” – incorrect

One common definition of “stimulus” is that the stimulus is the object in the world outside us, that causes the response to occur. To take a common example, if someone sees a tree, then this tree is a stimulus that causes the person to see the tree, as well as any other response that the person performs as a result of seeing that tree. But there are some problems with defining stimulus this way. First of all, how do we know that it is the tree that is the relevant object in that example? The tree reflects light from the sun. Isn’t it then the sun that is the object that caused the response? Or if we see a tree in the reflection of a mirror, isn’t it the mirror that is the object that caused the response?

When “stimulus” is defined as the object that causes a response, it is sometimes specified that it is not just any object, but the object that is the “ultimate cause” of the response. But we know from our previous discussion that really the only ultimate cause of everything in the universe is the Big Bang so this definition would not allow us to specify the tree in our example as being a stimulus. Sometimes, “stimulus” is defined more loosely as “the distal object” that causes the response. But then how do we know which object is the “distal” one?

Even if we were able to solve that question, there are many other types of phenomena that are not objects but still cause psychological responses to occur. For example, a response may be triggered by a sound, an electric current, by a thought, by a dream, by a feeling, by a sensation. A response may even be triggered by the absence of something which we expected to occur.

So “stimulus” cannot be defined as the object that causes the response. There are just too many stimuli that aren’t objects, and even when there are objects we don’t know which of these to choose as the stimulus. Let us therefore look at some other possibilities.

“A stimulus is the physical stimulation of receptors” – incorrect

Another common definition is that a stimulus is the physical stimulation of the receptors of the organism, described in terms of the physical energies involved. For example, if a researcher stimulates a receptor by an electric current and this causes the leg of the animal to twitch, then this electric current would be the stimulus in this example. These kinds of experiments were some of the earliest within the field of neurology, and it is where the term “stimulus” was first used in the study of animal behavior. It makes sense in such experiments to isolate what kind of physical stimulation that causes responses in an animal, and give these a name in the form of “stimulus”. There is a clear causal connection between the physical stimulation (the stimulus) and the subsequent movement of the animal’s limbs (the response). The application of the physical energy is under control by the experimenter, and so it is clear that as long as all other factors are kept the same, the only thing that determines whether the response occurs or not is the presence of that physical energy. Thus, defining stimulus as the physical stimulation of receptors allows us to use the term “stimulus” to investigate what kinds of responses that are caused by the various stimuli. In other words, such a definition allows us to formulate laws of how different stimuli and responses relate to each other.

If we use this definition then we could say that when we blink as a response to a puff of air in our eyes, then the stimulus in this case is the kinetic energy in the air that stimulates the sensory receptors in the eye. When we pull our hand away from a hot stove, then we can say that the stimulus in this case is the heat energy from the stove that stimulates our heat receptors in our hand. So in some examples this definition seems to make sense. But there are also some problems with the definition.

First, in our everyday lives, millions of receptors are stimulated at the same time. In the human eye alone, there are more than 100 million receptors. So, for example, when someone sees a dog there are millions of small receptors in that person’s eye that are stimulated by light energy. If the person responds to the dog with fear and running away, we will want to understand what stimulus caused this response. Should we then say that in that moment there are a million stimuli, that the person reacted to the millions of physical energies in their eyes? This kind of answer does not provide sufficient information. Before the dog appeared, there were also a million receptors being stimulated in the person’s eye, but the person did not become fearful and run away. So what is the difference between the million stimuli in one situation versus the other?

One way of trying to answer this question is to say that the difference is the pattern. In the situation with the dog, the stimulation of receptors has one pattern, and in the situation without the dog, the stimulation of receptors has another pattern. From this we could try to define “stimulus” as the pattern of physical stimulation of receptors. Each individual physical stimulation is just a “stimulus element” that can be combined with other “stimulus elements” in different ways to form different “stimuli”. But we would still have to be able to describe what that pattern is in each of the situations, otherwise we won’t be able to recognize when one stimulus is present as opposed to another stimulus. This is a lot harder to describe than one may think. For example, two dogs can look very different. They can have different shapes, colors, sizes. So the pattern when we see one dog can be very different from the pattern when we see another dog, yet the person still has the same response, i.e. gets scared and runs away. Also, if we look at the same dog from different perspectives, for example, from the side, from the front, from above, from below, the pattern is always different. What’s even worse is that if a cardboard box approaches the person and someone says “there’s a dog inside” then the person may become scared and run away, even though the visual pattern of receptors has nothing in common at all with those of a dog since a cardboard box looks nothing like a dog.

So how can we explain that the same response occurs, even though the pattern of physical stimulation is completely different between situations? Simply talking about physical stimulation does not capture the central properties of a stimulus. The same cardboard box can both cause a person to stay calm and cause a person to be scared and run away, depending on what the person believes is inside the cardboard box. Adding the thought of there being a dog causes fear, even when the physical stimulation of receptors is the same. In fact, the person could just as well lie in a dark room with no physical stimulation at all: if that person started to think about dogs, they could become scared.

What seems to be the common thread between all the different situations where the same response is observed is how the person experiences a situation. So let us therefore look more closely at defining “stimulus” in terms of experiences. Before we do so, it may be worth pointing out the difference between neurology and psychology. Even though the definition of stimulus as physical stimulation does not work for psychology, it works better when describing experiments in neurology. We must remember that neurology and psychology are two different fields. Psychology is the study of the mind, of animals that are alive, that experience the world. Applying an electric current to a dead frog and noticing that the leg twitches is therefore not an example of psychology. It is an example of physiology. Exactly how to think of the term “stimulus” in such cases will be clearer once we have defined its meaning in psychology. So let us therefore turn to how the term “stimulus” must be defined in psychology.

“A stimulus is something that is experienced” – correct but insufficient

Something that is undeniable for anyone who is trying to make sense of the world is that they have experiences. We experience the world around us, we experience our bodies, and we experience things in our mind. Our experience consists of a number of “parts”. For example, when we go for a walk we may experience a path in a field, individual trees, a sky, a sun, our body, other people around us, the sounds of birds, the sound of traffic, the sound of our footsteps, the smell of the flowers, the feeling of wind against our body, the feeling of our body moving, a feeling of heat, a sense of balance, the position of our body parts, a feeling of happiness, a thought about where to go next, a memory of when we walked this path yesterday, and so on.

As we live our lives we can discover that some of the things or events we experience cause some kind of reaction in us. For example, when we feel pain in our hand we immediately pull it away from whatever was causing the pain. Or when we feel that our eyes are dry, we automatically blink. Thus we conclude that there are events that seem to be triggered in us by some of the things we experience. It therefore seems to make sense to define “stimulus” as any “thing” or “event” that we experience. And we can then study in what ways different stimuli (i.e. different experienced “things” or “events”) cause us to respond or react in some way.

Going back to the example of a dog: If we are scared of dogs, then whenever we have the experience that a dog is near us, then our fear and desire to run away is triggered. The stimulus is the experience of there being a dog, the response is the fear and running away. Compare this to the attempt to define a stimulus as the physical object that caused the response to occur. When we defined stimulus this way, we could not explain why a person got scared when they mistakenly thought that there was a dog nearby, when there actually was no such dog. What causes a response to occur isn’t the object or event per se, but our experience (for example our belief) that there is such an object or event. Of course, most of the time our experience will reflect what is actually there. When there are dogs around we will often be able to perceive them by seeing, hearing or feeling them, and so the fear will appear because we become consciously aware of the dogs. But sometimes we will not perceive that there is a dog, even though there is one, and our fear may not be triggered despite the object being present. And sometimes we will think there is a dog, even though there isn’t one, and our fear will be triggered all the same.

Defining “stimulus” in terms of conscious experience also helps us solve the problem of how we can have the same response to a stimulus, even when the pattern of stimulation of the receptors are completely different in one situation compared to another. When seeing a small black dog on our right hand side, the activation of our receptors is completely different from when we see a big white dog on our left hand side. Yet, we perceive them both as the same kind of animal: a dog. The explanation for this is that how we experience and respond to things depends not only on how the receptors in our senses are activated at that moment, nor on what is physically present around us at that moment, but also by our previous experiences, our learning history, and how we have learnt more general or abstract ideas. Let’s look at how that works.

Our mind is constantly trying to predict what stimuli will appear in the next moment, and via this mechanism it is able to connect things we experience to form more advanced concepts or experiences. So when we see a dog from one perspective, and then move around and see it from a slightly different perspective, we learn that these experiences are just two different perspectives of the same object. Through such experiences our mind builds up a more general experience or “idea” of the dog such that when we view the dog from one perspective we don’t experience just that perspective, instead we experience it as an object that has several possible perspectives. We see the whole dog “Fido” or “Bella”, not some two-dimensional image or a collection of colors and lines. And when we see one dog behave in a certain way, and at a later time see another dog behave in similar ways, we learn that these two dogs are the same type of animal. So when we see a dog we don’t just have an experience of that specific dog, but also have an experience of it being a dog among many. In other words, we don’t just experience it as being “Fido” or “Bella”, but also as “a dog” more generally. So for example, if we have been bitten by one dog, then we expect other dogs to bite us too, because of us having learnt that different dogs often behave in similar ways. So our personal history of learning things about the world causes our experience in any given moment to consist of more than is physically present at that moment.

So defining “stimulus” as something we experience allows us to explain how and when stimuli cause responses to occur when other attempts to define the term fail. But simply saying that a stimulus is something that is experienced is not a sufficiently detailed definition. Earlier we described our experience as consisting of a number of “parts”, and said that a stimulus is such a “part” of our experience. But what makes something a “part”? If we have a person standing in front of us, is that person a stimulus, or is the person’s hat, t-shirt, shorts and shoes individual stimuli? When are these things “parts” of something else, and when are they “things in themselves”? Is the person’s eyes stimuli or is it the person’s whole face, or head that is a stimulus? Is there one stimulus in front of us, or 1000 stimuli? If we can’t answer such questions then our definition of “stimulus” is not precise enough. Let us therefore see how we can make it more precise.

“A stimulus is anything we experience as a coherent phenomenon” – correct

What makes something that we experience one stimulus as opposed to a collection of several stimuli? How do we know how to divide up the world we experience in its “correct parts”? The answer is that our experience tells us the answer. When we experience the world around us, some things are experienced as more or less one “thing” or event, being more or less separate from other “things” or events. So a more precise definition of stimulus is that it is anything that is experienced as a coherent phenomenon, i.e. that is experienced as “a thing in itself” and not merely as a part of something or as just some jumbled nonsense. But how we experience this will depend on the specific situation.

When we see a person, we could experience the whole person as a single stimulus. For example, if we see a person from far away walking alone in a big field, then in contrast to the surroundings the person stands out and is experienced as separate from the surroundings. Thus the whole person is experienced as a single stimulus. We cannot see enough details of the person for any of these details to stand out and be perceived as separate stimuli. If we see a person from far away surrounded by a thousand other people, then instead we may perceive the whole crowd as a single stimulus, where the individual people are experienced more vaguely or indirectly as parts of that stimulus. If we see a person very close up and where their head lines up with ours, then when looking at their face we may experience the face or the head as a single stimulus, and the rest of the body more vaguely as a somewhat separate stimulus. If we focus our attention on the eyes of the person, then the eyes can be experienced as separate stimuli, while the rest of the face is experienced as another stimulus. If we see two people coming towards us that we have met many times before and know that they are a couple who do everything together, then we may see these two people as a single stimulus. “Oh, look here come the Hendersons!”

What makes something a stimulus in a specific situation is thus determined by factors like how it compares or contrasts to the surrounding stimuli, how we focus our attention, and our previous experiences involving the stimuli. When we experience something as a stimulus, we may call the parts or details of that stimulus “stimulus elements”. For example, when we see the face of a person as a single stimulus, then the eyes, ears, mouth, nose, hair, etc are the stimulus elements of that stimulus. If we focus our attention towards any of the stimulus elements they can become stimuli of their own, but in the moment where the whole face is the stimulus, the stimulus elements are not technically stimuli on their own. The concept of “stimulus” is thus very dynamic, always depending on the specific situation under interest. There is no absolute or “always true” stimulus that can be established “in general”. What counts as one stimulus for one individual, in one context, at one point in time, does not have to count as one stimulus for another individual, or in another context, or at another point in time. This fact can be hard to accept since in science and philosophy we often want to establish absolute truths and general statements. This doesn’t cause any problems for science or philosophy though, since the definition of stimulus is still an absolute and general truth, and describes phenomena to which absolute and general laws can be applied. It is only that what counts as a stimulus in a specific situation always is relative, because our experience is always affected by contextual factors.

Another concern may be that the boundaries of a stimulus often are fuzzy. For something to be a stimulus it isn’t necessary that the phenomenon is 100% coherent and 100% separate from all else. Instead, something can be more or less of a stimulus, depending on the degree to which it is coherent and separate from other phenomena. For example, a mountain can be a stimulus even though it isn’t entirely clear exactly where the mountain begins and the ground ends. The closer we are to the mountain, the harder it will usually be to point to the exact spot where the ground stops and the mountain begins. But the further away we are, the more the mountain is experienced as separate from the ground, as the area of uncertainty is less prominent at such distances. We will rarely be in a situation where there is a 100% clear cut between the mountain and everything else. Still, we can experience the mountain as a “thing in itself”, i.e. as a stimulus.

Summing all this up, technically it might be more precise to say that: A stimulus is something that is experienced as a more or less coherent phenomenon in a specified situation. But the less technical definition is good enough, as long as we understand the nuances of what it means. This definition is true of all stimuli, but it may be useful to know more than this general definition in order to understand properly what a stimulus is. We also need an understanding of two different types of stimuli: external stimuli and internal stimuli. These have very different properties, they cause very different types of responses, and do so through very different mechanisms. Let us therefore take a closer look at them.

External and internal stimulus

There are two broad types of stimuli:

An external stimulus is a stimulus that exists outside the mind, in other words, out there in the world. In other words, the stimulus is external to the mind.

An internal stimulus is a stimulus that exists only inside the mind. In other words, the stimulus is internal to the mind.

In order to make sense of these different types we must first remember that we have defined “stimulus” in such a way that when we use this term we are not referring to the experience itself, but to the phenomenon (the “thing” or “event”) that we are having an experience of. The definition states “A stimulus in anything that is experienced as a coherent phenomenon”. And so the things we experience can exist in different forms and have different properties. We may experience things that exist in the world outside our mind, like trees, the sky, the sound of a bird, and we may experience things that exist only inside our mind, like a feeling, a memory, a hallucination.

When a stimulus exists outside the mind it has a physical existence. It is made up of physical matter or energies, and follows the laws of physics. When a stimulus exists inside the mind it has a mental existence. It is made up of conscious experience, and follows the laws of psychology. Stimuli that exist outside our mind (external stimuli) continue to exist even when we are no longer experiencing them, while stimuli that exist inside our mind (internal stimuli) cease to exist when we are no longer experiencing them. For example, when we fall asleep we stop experiencing the house around us, but the house continues to exist all the same. But when we experience a magical house in our dreams and then wake up, the imagined magical house ceases to exist as soon as we stop thinking about it. It existed only in our mind.

External and internal stimuli also have different forms of causal power. External stimuli can cause things to happen even when we have no experience of them, while internal stimuli can only cause things to happen while we experience them. For example, since an apple is an external stimulus, it can fall from a tree and land on the ground, even if no one is there to see it. And since the thought of a unicorn is an internal stimulus, it can cause a person to think of a rainbow, which is another internal stimulus, but it cannot cause a physical rainbow to appear. Thanks to this, external and internal stimuli can bring about different types of psychological responses, and differ in how they do so.

External stimuli can only cause one type of psychological response called “sensation”, and it does so by stimulating the senses of an organism via transmission of physical energies. For example, when light enters our eyes, the light energy stimulates the millions of receptors at the back of the eye and brings about millions of consciously experienced tiny dots of different colors and intensities. When a sound wave enters our ears, the sound energy can stimulate thousands of receptors inside the ear, resulting in a conscious experience of thousands of individual frequencies. External stimuli thus only cause raw sensory data to occur. Each sensory data (for example, each dot or frequency) is an internal stimulus or stimulus element, which corresponds to a particular physical energy in a specific location. But on its own it usually doesn’t make much sense. Instead of seeing a million dots, we would prefer to see objects, landscapes, animals, movements. Instead of hearing a thousand frequencies we would prefer to hear voices, songs, sounds. This is what happens after the external stimuli have been sensed by the mind and thus the creation of internal stimuli, which we will turn to next.

Internal stimuli cause all the other types of responses aside from that of sensation. This includes responses like perception, behavior and emotion. When internal stimuli or stimulus elements have been created by external stimulation, they first set off the response of perception. Perception is the process where the individual stimulus elements of sensation are put together to more meaningful wholes. For example, when a number of black dots are placed next to each other in a line, this creates the experience of a black line, instead of just a collection of black dots. When we in a certain moment hear a number of frequencies that have a relationship with each other in the form of a harmonic series, this creates the experience of a tone with a certain timbre, instead of just a collection of frequencies. The process of perception happens so quickly and automatically that we almost never realize that there is a very short stage of perception where we experience a vast number of raw sensory stimuli. Another reason we seldom experience a collection of raw sensory stimuli is that the mind has the capacity to quite accurately predict which stimuli will appear in the next moment. This has the effect that the more meaningful parts, the more coherent wholes, are experienced first, and only the sensory data that don’t match the prediction are experienced as raw sensory stimuli for a short while before being perceptually processed. We will look at this in more detail when we get to the prediction and learning principles of the mind.

The perceptual experience that occurs as a result of this two-step process is the conscious experience of the external stimuli. In other words, when something outside the mind, like a tree, stimulates our receptors, for example by reflecting light towards us that is absorbed by the receptors in the eyes, then this creates internal stimuli which set off a perceptual process which in turn results in an experience of seeing the tree.

Now, at this point, it is really easy to be confused. Is the experience of seeing the tree an external stimulus or an internal stimulus? The way the process is described makes it sound like the external stimulus (the tree) caused an internal stimulus (the experience of the tree), and that internal stimulus is the external stimulus? What? So let’s slow it down a bit and be really careful here about what is going on. We must remember the definition of “stimulus”: A stimulus is anything that is experienced as a coherent phenomenon. And what is experienced depends on the specific situation or context. Let’s apply this to the above description. When we talk about something outside the mind (like a tree), then what is in focus in our conscious experience is that something (e.g. tree) that we know exists outside our mind. Thus, in this specific situation we are talking about an external stimulus. When we just a few moments later talk about an experience of seeing the tree, then what is in focus in our conscious experience is the experience itself of seeing a tree. An experience exists inside our mind, and thus in this specific situation we are talking about an internal stimulus. We have made a subtle shift in situation that can be hard to notice. First we talk about the tree (external stimulus), and then we talk about the experience of seeing a tree (internal stimulus). These two stimuli are of course very intimately linked. The content of the internal stimulus of “seeing a tree”, i.e. what this stimulus is about, is the external stimulus “the tree”.

This leads us to another fundamental property of stimuli: Each internal stimulus can be viewed on two different levels:

The content level: What the conscious experience is about

The meta level: What the conscious experience is itself

For example, let’s take the experience of hearing a song. The content of this experience is the song itself. This is an external stimulus, something that exists outside the mind. But the experience of hearing a song itself is an internal stimulus, this is the meta level of the stimulus. Another example is the experience of thinking about a unicorn. The content of this experience is in this case an internal stimulus, since the unicorn only exists in our minds (if we are not talking about a drawing of a unicorn or something like this). The experience itself is also an internal stimulus, i.e. a thought. So in this case, both the content level and the meta level describe internal stimuli.

We can formulate the property another way from the perspective of external stimuli. Each external stimulus exists outside the mind, but every time we consciously experience this stimulus, this experience itself is an internal stimulus. Or to say this another way: an external stimulus can only be experienced in terms of it being the content of an internal stimulus.

It is okay to be really confused about this for a while. The distinction is very subtle, and in fact has been missed by philosophers for thousands of years. We are so used to thinking about the content of our experience that we tend to forget that whatever we are having an experience about, it is also an experience in itself, and we can shift focus between the content level and meta level for different purposes. In fact, this shift is central for the therapy of metacognitive therapy. Realizing the difference between a catastrophic scenario we are thinking about, and the fact that we are having thoughts about a catastrophic scenario. Regardless of how distressing the catastrophic scenario is, we still have the power to choose how we deal with our thoughts of the catastrophic scenario. Even if we can’t control the scenario, we can control our thinking.

An example that is a little more tricky is when we think of a memory, for example we could think about the last time we brushed our teeth. The event really took place (unless you are a person who has never brushed your teeth, in which case you might want to see a dentist). So in this sense, the content is about an external stimulus, but the situation is different from when we are actually standing in the bathroom with the toothbrush in our hand, and perceive the event directly. Another way to contrast these types of experience is to compare the situation of looking at what is in front of us in one moment, then closing our eyes and focusing on our memory of what we just saw when we had our eyes open. Both times we are focusing on the same external stimulus, but in the first moment we are focusing on the direct experience of the external stimulus (our perception), while in the second moment we are focusing on the indirect experience of the external stimulus (the memory). The same kind of distinction can be made when the content is an internal stimulus. For example, we can experience a feeling of happiness directly, and we can think about the memory of that feeling, in other words, the feeling is experienced only indirectly. Thus, the content of an internal stimulus can have two different types of relationships to its content:

Direct experience: When we experience an external or internal stimulus directly, for example when we perceive an external stimulus (like a tree or song) that is present in that moment, or experience an internal stimulus (like a feeling or mental image) that is present in that moment.

Indirect experience: When we experience an external or internal stimulus indirectly, for example when we remember something that we experienced before or when we are told about something that someone else has experienced.

So when we talk about perception, we are talking about an external stimulus being experienced directly. We can explain how this occurs by describing the two-step process that is involved.

The first step: An external stimulus (like a tree) causes a large set of internal stimuli (a collection of tiny dots) which each is about a tiny part of the external stimulus. In other words, the content of each tiny internal stimulus is a tiny external stimulus in the form of a “dot” in the world outside the mind. The large set of internal stimuli is thus the response to the external stimulus. And this occurs through the physical mechanism outside our mind where a large number of light waves travel from the external stimulus and transfer their energies to the receptors in the eye.

The second step: The large set of internal stimuli in turn cause a coherent internal stimulus to occur that is about the external stimulus as a whole. The larger, more coherent internal stimulus is thus the response to the collection of smaller internal stimuli (which thereby become stimulus elements, i.e. parts, of the coherent internal stimulus). This occurs via psychological mechanisms, i.e. through the activation of a network of relations in our mind between stimuli and responses (which we will look at more closely later).

Even though this explanation is the technically correct one, we can often use a shorter version when talking about perception to get the main point across:

An external stimulus (like a tree) causes an internal stimulus to appear (the experience of a tree), where the external stimulus (the tree) is the content of that internal stimulus (the experience of the tree).

A mix of external and internal stimulus elements

When we have an experience, parts of that experience may be external stimulus elements and parts may be internal stimulus elements. For example, we might see a cat from a distance and think that the cat is wearing a hat, but as we get closer we see that it was a flower that the cat was hiding under. In such a case, the part of the cat that we experienced as a hat was a misperception, an imagination, merely something that existed in our mind. While the rest of the cat was in fact as we perceived it to be. So the cat itself was an external stimulus (or stimulus element), while the hat was an internal stimulus (or stimulus element). Or if we see something in our home in the dark we may think that we see an intruder, but in fact it was just a coat hanging on a coat hanger. The coat is thus an external stimulus element, but the head, arms and legs that we think that we see are internal stimulus elements, mere imagination.

Being mistaken about a stimulus

What the examples show is that it is not always clear whether the content of our experience is something outside our mind (an external stimulus) or merely something inside our mind (an internal stimulus). Sometimes we can be almost completely wrong about what we experience. Seeing a bush from afar, it can sometimes look like a cow (this has happened to me on several occasions). But as we get closer we discover that it is in fact a bush, and not a cow. We were incorrect in our previous judgement. First we thought there was an external stimulus in the form of a cow, and then we thought there was an external stimulus in the form of a bush. When we come to the realization that it is in fact a bush, we realize that our initial experience was not a correct perception of something outside our mind, but instead more of a hallucination or imagination. The only parts of our initial experience that was actually correct and corresponded to the actual external stimulus were the colors and shapes.

That fact that we can be mistaken about stimuli may seem to pose a threat to how we have defined “stimulus”. If we have defined “stimulus” as something that is experienced as a coherent phenomenon then shouldn’t a stimulus always be “correct” according to such a definition? If we experience something as being a cow, and a stimulus is that which is experienced, then the stimulus must be a cow, right? How could we ever claim that this stimulus is incorrect if the cow fits the definition of “stimulus”? To see the solution to this question we must remember that saying that something is a stimulus is not the same as saying that the stimulus exists outside our mind the way we experience it. There is nothing in the definition of “stimulus” that says that whatever we experience is an external stimulus. Determining whether a stimulus is external or internal can only be done by collecting more experiences of the stimulus. When we see a stimulus from a closer distance, or from another perspective, we are able to see more details. These details allow us to determine the properties of a stimulus more accurately. When we approached what we thought were a cow we could see that it consisted of branches and leaves and not flesh and bone. When we think back to the previous moment when we thought we saw a cow, we can now see that it was in fact this bush that we were perceiving in an incorrect manner. So retroactively, we can now conclude that the cow-stimulus was an internal stimulus (or at least a stimulus where most of the stimulus elements are internal), while the bush-stimulus was the external stimulus present in that situation. We change our opinion on what the external stimulus was.

Describing this in another way, we can never deny that we have such and such experience, for example we can never deny that we have the experience of there being a cow, but we can deny whether the content of that experience really has the properties that we perceive them to have. In other words, we can deny whether the experienced cow is actually something outside our minds or merely our imagination. The fact that we can be mistaken about what the external stimulus is in a certain situation is of course unfortunate, but it does not mean that there is any problem with how we have defined the term “stimulus”. Defining “stimulus” in any other way would not have prevented us from making the mistake anyway.

A stimulus is defined from the perspective of a specific organism

The distinction between external and internal stimulus, and between content level and meta level, allowed us to show that even though the definition of “stimulus” is “anything that is experienced as a coherent phenomenon”, a stimulus can still be something that exists outside the mind. The fact that “experience” is a fundamental part of the definition doesn’t force us to get locked inside our head. But still, the fact remains that something can only be classified as a stimulus as long as it is experienced directly or indirectly by someone. This means that, technically, a stimulus is always defined from the perspective of a specific organism that experiences the phenomenon. This is an unusual property in science and philosophy, where we are used to thinking that scientific and philosophical phenomena are independent of who is talking about them. This property therefore needs to be investigated closely in order to provide us with a solid understanding of the nature of stimuli.

Even if I talk about an external stimulus like a tree, this external stimulus is experienced in a specific way by me. I see it from a specific perspective, I am aware of certain features of the tree, I have specific memories related to the tree. If I have only seen the tree from one side, and my friend has only seen the tree from another side, if I am color blind, but my friend is not, if I have good eye-sight, but my friend has blurry vision, then the tree appears very differently to me and my friend. Even though the tree is the same physical object, the properties that the tree appears to have according to me are very different from how my friend sees it. We agree on some properties, for example the fact that it is made of wood, that it is placed in this spot, that it has branches, and so on. But not on others, for example that the tree is colorful, that has intricate patterns on its leaves, and that it has a certain shape. In this kind of situation it is not the case that I am correct and my friend is wrong, we both have incomplete knowledge of the tree and so the specific perspectives we have differ wildly. Let us now say that the side of the tree that I see has a haunting look, like something out of a horror movie, while the side of the tree that my friend sees is more pleasant. So when I see the tree I get scared and run away, but my friend sits down in the grass and admires the beautiful tree. It would seem like we have very different responses to the same stimulus, but in fact there are two different stimuli, with overlapping stimulus elements and properties. One of the stimuli is a haunting tree, and the other is a pleasant tree. If me and my friend had switched sides, it is quite likely that our responses would have switched as well. My friend would have been scared and run away, and I would have sat down in the grass to admire the tree. Thus, in order to understand and explain responses of an organism, we must also define the stimulus from the perspective of that specific organism. It would have been incorrect of my friend to say that I got scared of a pleasant-looking tree, since the stimulus was not a pleasant-looking tree in my case. A stimulus must be a stimulus from the perspective of the organism if we want to explain the psychology of that organism.

Similarly, there can be situations where I and someone else may disagree on whether there is any stimulus at all. For example, my friend may be deaf and so when I hear a bird singing, my friend does not. So the bird song is a stimulus from my perspective, but not from my friend’s. To take another example, a bird can sense the magnetic field of earth, while I cannot. So from the bird’s perspective the magnetic field is a stimulus, but not from mine. Of course, I could use various technical instruments and discover that there is a magnetic field. In this case, the magnetic field would become a stimulus from my perspective too, although only experienced indirectly. Similarly, I could sign to my friend that there is a bird singing, and so the bird song would then become a stimulus from my friend’s perspective too, although only via indirect experience.

Knowing if something is a stimulus for another organism

Defining “stimulus” as anything that is experienced as a coherent phenomenon does bring about a great difficulty: we only have direct access to our own experience. The term “stimulus” is supposed to allow us to explain the psychology of all organisms, which includes ourselves, other people, animals and other organisms. The trouble is that we don’t have any way of looking into the conscious experience of anyone else. How could we then determine whether something is a stimulus when talking about another organism?

The problem of knowing what goes on inside someone else’s mind is one of the reasons why the field of behaviorism was created at the beginning of the 1900’s with the goal of making psychology a discipline where the mind was irrelevant. The field focused only on what could be observed from the outside. Whether a stimulus was experienced or not didn’t matter. And the only responses that were of interest were the organism’s visible behavior, not the organism’s feelings or thoughts, etc. It would of course have been great if it was possible to create a complete psychology this way, but unfortunately it is not. There are a number of reasons for this.

Firstly, a stimulus can be wholly internal, and so the stimulus cannot be observed from outside. For example, a person may fantasize about a magical world for hours. The fact that this person forgets to eat dinner as a result of this cannot be explained as a reaction to any external stimulus present in that situation. A classical behaviorist may try to solve this problem by explaining that these internal stimuli appear as a result of external stimuli that were present at previous times in the person’s life, and try to trace the causal chain to those stimuli. Thus, they might say that the person didn’t eat their dinner tonight because during the person’s childhood there were several books, films and stories that that the person read, saw or heard. This kind of answer isn’t particularly satisfying. The explanation only makes sense if we add that these events in turn inspired the person to fantasize about magical worlds, which the behaviorist cannot say, since this is something that goes on in the mind. Another problem is how to explain why a person with aphantasia, i.e. the inability to visualize things in their mind, doesn’t end up in a similar situation as the person with the ability to visualize. Even if two people had been exposed to the same external stimuli, the person with the ability to visualize things in their mind would spend time doing so, while the person with aphantasia would not. A classical behaviorist could not explain this difference in behavior, since the only difference between the two people is their inner experience, and classical behaviorism cannot talk about inner experience.

Secondly, classical behaviorism can never explain what happens in any specific situation, only what happens on average over a number of similar situations. In experiments of classical behaviorism a rat may be placed in a box and be presented with a lever that the rat can press to get some food. On some occasions the rat will press the lever, on other occasions it will not. What can be observed is that on average, a rat presses the lever more often if it results in food, compared to if it results in an electric shock. When limited only to what is visible to the observer, there is no way to tell the difference between a moment where the rat presses the lever, and when it does not, since everything in the surrounding remains the same. There is no external stimulus that shifts between a moment where the rat decides to press the lever, and when it does not. The difference is internal. For example, the rat’s level of curiosity may shift from one moment to another, it may be focused on or distracted by something else in the box for a while, the rat’s hunger may shift. These kinds of internal shifts average out when a situation is repeated 100 times, and allows the researcher to say something like “When the rat is presented with a reward it presses the lever 45 times per minute on average, but when the rat is presented with a punishment it presses the lever only 5 times per minute on average. Thus the reward caused the rat to press more often.” But in our everyday lives, the exact same situation rarely appears again and again. Instead, life evolves, with new situations appearing all the time. We want to be able to explain why someone did something in a specific situation, not what it most likely would have done on average if it had been in the situation 100 times. We want psychology to be an exact science. We can compare this to a field like physics where it would have been completely unacceptable if we couldn’t explain why an apple fell from a tree in a specific situation. Imagine if the physicist’s explanation was that when apples are in a situation of hanging on a branch, they will on average fall down as a result of gravity sometime during that year. We would demand the more exact explanation that a specific apple falls from the tree at the specific moment when the force of gravity acting on the apple is stronger than the electric forces connecting the apple to the branch.

Thirdly, classical behaviorism is not able to define the term “stimulus” in a coherent manner. The most common attempt to define “stimulus” in classical behaviorism is as something that can cause a response. We have already looked at the problem of defining “stimulus” this way. There are an infinite number of things that could be said to be the cause of some event. The definition is too general for us to be able to specify a specific phenomenon.

Let us therefore look at how we may deal with the issue of not being able to look directly into someone else’s mind, while holding on to the definition of “stimulus” as anything that is experienced as a coherent phenomenon.

I am not the only conscious being

There are good reasons to believe that I am not the only organism in the world who has conscious experience. The fact that people before my time have come up with words like “consciousness” and “experience” suggests that they had conscious experience and wanted to have words that refer to this. The fact that people today use such words, that others understand what I mean when I talk about having experiences, the fact that even small children talk about things like “What if my color red looks like your color green?”, suggests that people in general have conscious experience. Thanks to our ability to communicate with language we can tell other people about our experience. We don’t need to look directly into another person’s mind in order to figure out if they are conscious, we can just ask them about it. In the future we may have figured out what mechanisms in the brain are responsible for conscious experience, and then we could indirectly see whether some organism is conscious by looking at their brain activity. But even when we lack this scientific knowledge and technology, we can be rather certain that at least other humans have conscious experience. Other organisms are more difficult to deal with, since their lack of language means we cannot ask them.

Many people believe that animals that are similar to us humans have conscious experience. Monkeys, gorillas, dogs, cats. When we interact with such animals, they behave much like humans would. They seem to understand us, to have a mind of their own, and are able to empathize with us. We also know that their brain is similar to ours, and we know that the brain is the seat of consciousness. But as we look at animals and other organisms that are less similar to us, we are more unsure. Is a worm conscious? Many people do not believe that worms have conscious experience. But worms do have a brain, though it consists of very few neurons, compared to that of a human brain. Since we haven’t yet discovered what brain mechanisms correspond to conscious experience, there is not yet any way to know whether an organism like a worm has conscious experiences or not. It is possible that only organisms with a certain level of complexity in their brain structure have conscious experience. Or it could be that all organisms with at least one neuron have conscious experience. How are we to deal with this uncertainty, and could it cause any problem for our definition of “stimulus”?

Stimulus from several perspectives

Research in psychology often involves presenting something to an organism and observing how it reacts. For example, a researcher may place some food in front of an organism and see how it reacts. In these experiments, the thing that is presented to the organism is described by the researcher as “the stimulus”, and the way that the organism reacts to this stimulus is described by the researcher as “the response”. If the organism is conscious then the food is a stimulus from the perspective of the organism, but if the organism isn’t conscious then what has been described as “the stimulus” isn’t actually a stimulus according to our definition. Here is how we can deal with it.

If the organism doesn’t have conscious experience, then we aren’t actually talking about psychology. The defining property of psychology is the presence of a mind, a conscious being, some being that acts, that feels, that wants, etc. If an organism lacks such properties, then it isn’t much more than a physical system with causes and effects, like a calculator. If we observe a physical system, for example how a light turns on when we press a certain button, then we can observe that there is a cause (the pressing of a button) and an effect (the light turning on). We can observe that there is a law that this particular effect always occurs when the particular cause occurs, and so we could explain and predict certain events that we observe regarding the physical system. So if an organism is of such a simple kind that it lacks conscious experience, then describing how it responds to certain events is like describing a mere physical system. So let’s say that worms lack conscious experience. If we poke a worm with a stick and observe that it recoils in response, then we can say that the poking with a stick causes a recoiling effect. There isn’t really any need to say that the poking with a stick is a stimulus. It adds nothing more than it would for us to have said that the pressing of a button is a stimulus. If we want we could instead use general scientific terms like “independent variable”, the variable that is under our control, and observe how this affects the “dependent variable”, i.e. the effect.

But if we do decide to use the term “stimulus” when talking about an organism like a worm, because we are uncertain of whether the organism is conscious or not, then there is a way to interpret the use of this term that avoids any problem.

Different definitions in different fields

The term “stimulus” can have different definitions depending on the area of use. It is common for words to have slightly different meanings in different contexts. For example, the word “date” can refer to a day in the calendar, the act of determining how old something is, the event of going out with someone for romantic purposes, the person we are going out with, and even a sweet-tasting fruit. In science, where it is important to be very specific in what is meant by a word, it is common for words to have slightly different definitions depending on the specific scientific field. For example, the word “sex” within genetics refers to the presence of X or Y chromosomes (XX is female, XY is male). Within anatomy, however, it refers to the genitalia of the person. In the context of reproduction, “sex” refers to the ability to produce eggs or sperm. Within sociology it refers to the social construction of categories which includes identity and social roles. Sometimes the different definitions align, and sometimes they don’t. For example, a person with female genes can have male genitalia. It is not the case that one of the definitions is “the correct one”, and all others incorrect. They are different definitions that serve different purposes in different fields.

Thus, the term “stimulus” can be defined one way when we talk about psychology, and another way when we use it in other contexts. For example, within the field of physiology, “stimulus” is usually defined along the lines of “a thing or event that evokes a specific functional reaction in an organ or tissue”. So, for example, when the skin gets sunburned, the sun is the stimulus, and the sunburn is the response. This happens even if the person isn’t consciously aware of the sun (maybe the person has fallen asleep in the sun), because the effect of being sunburnt isn’t a psychological response, it is a physiological response. So for these kinds of causal effects it is fine that “stimulus” is defined differently.

But here is a major caveat: changing the definition of “stimulus” also changes what laws apply to the stimulus. The causal mechanisms of physiology are not generally the same as the causal mechanisms of psychology. As we will look at later, in psychology the stimulus is connected to responses via psychological relations, and the way that these relations are activated and changed are determined by psychological laws. When we talk about a stimulus in the physiological sense instead, the laws that apply to such stimuli are different. They don’t follow the laws of psychology. When the sun causes the skin to get sunburnt this happens as a result of ultraviolet light waves damaging the cells. This kind of effect abides by the laws of physiology instead. We can compare this to a situation where the person is feeling happy because the sun is shining. In this case the sun must be a stimulus in the psychological sense for that person, i.e. something that is experienced as a coherent phenomenon, in order to explain the psychological response (feeling happy). And the connection between the stimulus and response in this case abides the laws of psychology.

The interesting thing here is that even if “stimulus” is used in a non-psychological context, it is still also a stimulus in the psychological sense from the perspective of the observer. The only way for someone to give a description of a physiological cause and effect is if this person in some way experiences the causes and effects involved. So when the sun is described as a (physiological) stimulus that causes the skin to be sunburnt, the sun is also experienced as a coherent phenomenon by this observer, and therefore is a psychological stimulus from the observer’s perspective. In this sense, a stimulus is always primarily a psychological stimulus, regardless of whether it is then used to discuss how it affects something in a non-psychological way. We should also take note that the effect that is observed by the observer is also a stimulus from their perspective. The only way for the observer to talk about the sun causing a sunburn is if the observer has some kind of experience of the sunburn too, i.e. that is experienced as a coherent phenomenon. So from this perspective, when we describe a physiological stimulus causing a physiological response, both the stimulus and response are psychological stimuli to us in the first place. This means that we need to be careful when claiming that something is a stimulus. From whose perspective are we saying that it is a stimulus? From our perspective, or from someone or something else?