How Do We Acquire Wisdom?

If we are to achieve the goal of A Wiser World to make the world a wiser place it is not enough to know what wisdom is, we must also know how to get it. Let us dig into this question next, and see if we can find the first principles of acquiring wisdom.

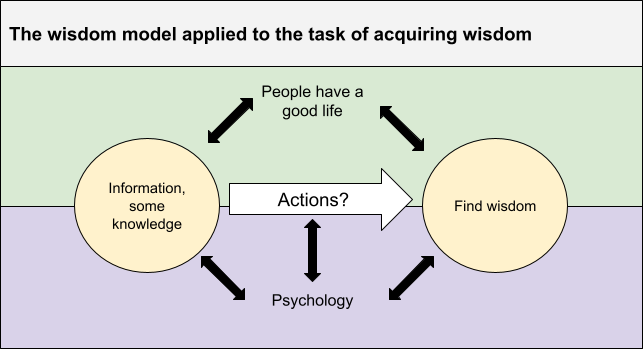

The wisdom model applied to the task of acquiring wisdom

We established the wisdom model as a way of getting an overview of what wisdom consists of. Now that we are trying to figure out how to acquire wisdom, we can apply this model to get an overview of what we need to figure out in order to “be wise” about finding wisdom.

Figure 1. The Wisdom Model applied to the task of acquiring wisdom

We can begin with the goal situation, which is the most obvious one: Our goal is that we have found wisdom. The reason why this would be a desirable goal is because our overarching value for this project is for people to have a good life. Wisdom is knowledge of how to lead a good life, and so if we are able to find wisdom, this will be in line with our value. For the same reason, we can see that our current situation, where we don’t have wisdom but instead a lot of information and some knowledge, is not as desirable. In order to be wise about finding wisdom we also need to understand how the world works in some regards. In this case, this concerns knowledge of psychology in particular. The piece that is missing is the action. What is it we need to do in order to go from the current situation to the goal situation? This is what we need to figure out. Furthermore: the knowledge we are now looking for should hold true over as many different situations as possible, and over as long a time as possible. So let us take on this task.

How do we acquire knowledge?

Since wisdom is having knowledge that helps us lead a good life, let us first look at how we acquire knowledge more generally.

The learning process of the mind

In order to find the first principles of something, we want to dig down to fundamental truths at the core of the topic at hand. In the case of finding the first principles of acquiring knowledge, we can turn to fundamentals of how learning occurs in our minds. As we will see when we look at the first principles of psychology, our mind is learning in every single moment through a process that consists of the following steps:

1. Observation: The mind observes what happens. For example: A ball rolls over the edge of a table and falls to the ground.

2. Comparison: The mind compares what happened with what it predicted would happen. For example: The mind expected the ball to continue rolling in the air, because the person had never seen a ball roll over an edge before.

3. Hypothesis: The mind forms a new hypothesis or revises the old hypothesis which had given rise to the incorrect prediction. For example: “When a ball rolls over the edge of a table, it falls to the ground (instead of continuing to roll in the air)”.

4. Prediction: The observation also gives rise to predictions for what will happen in the next moment. For example: When the ball falls to the ground it will bounce.

The cycle then repeats, where the mind observes what happens in the next moment, and compares this to the new prediction, and so on.

When we act, the prediction that the mind makes about what will happen next includes what consequences it expects the action to have. For example, if we decide to reach out the arm towards the ball, the prediction may be that what we will observe in the next moment is that the ball falls into our hand. So in cases where we are not just passive observers, we can add another step in the cycle.

5. Action: The action is performed. For example: The arm is stretched out towards the ball.

These steps occur automatically over and over in every single moment and allows us to learn about the world. The comparison, the creation of a hypothesis and the prediction all happen subconsciously. Usually we don’t notice that the mind is doing this. It is only when the prediction is considerably wrong that we become aware of the fact that the mind was predicting something, and we may experience this as a feeling of surprise.

The knowledge method

But when we want to be more deliberate in what we learn, such as when we tackle more complex questions, then we can follow the same steps in a more conscious manner.

- Observation: Make some observations. You could either just use your senses, or you could use some tools that would help you make more accurate observations.

- Comparison: Compare the observations against your expectations. Were you surprised by the observations? If so, was that because you had no expectations and simply experienced it as new information? Or did the observations contradict your expectations? If so, what were your expectations, and in what way did your expectations differ?

- Hypothesis: Come up with a hypothesis, or revise an old hypothesis. How would you explain the observations? Why do you think you observed the things you observed? Are there several possible explanations? Could it even be that the observation was a mistake, that it was an accidental event that isn’t normally the case?

- Predictions: Make predictions from your hypothesis. How could you test your hypotheses to see if they are correct? Or if you have several hypotheses: to test which of them seems to be the most correct one? What action or observation could you perform? What would the hypotheses predict would happen if that action was performed?

- Action: Carry out the test to produce observations that can show whether things are as the hypothesis predicted or not.

And then repeat the cycle.

We can call this “The knowledge method”, and use the acronym OCHPA as a way to remember the steps more easily.

Let’s apply the method to an example. We are interested in figuring out how to fish. Being complete beginners we know nothing about fishes or fishing tools. We can then begin by making some observations. We observe that other people who manage to catch some fish use some kind of stick with a string that goes into the water. We are a little surprised by this, but not too much, because we have seen people use other tools to catch animals, so we think it makes sense to use some kind of tool for fishing too. From this we decide upon the hypothesis that in order to fish we need a stick with a string on it. So we find a stick and attach a string to it, and from our hypothesis we now make the prediction that as we lower the string into the water we will catch some fish. But even though we do so, we observe that we do not catch any fish. Our prediction failed, and so we conclude that we need to revise our hypothesis in some way. We decide to take a closer look at the other fishers and notice that at the end of their string there is a hook. So our new hypothesis is that a stick with a string with a hook at the end, is what is required to catch a fish. And so step by step we make new observations, compare the observations to our predictions, update our hypotheses, make new predictions and perform new actions in order to test our hypotheses and increase our knowledge.

In order for us to be successful in acquiring new knowledge it helps if we do all these things with care. If we are sloppy when making observations then we might not catch all the necessary details, or even be mistaken, thinking that we saw one thing when in reality it was something else. If we are sloppy when comparing our observations with our predictions we may think that the observation confirmed our hypothesis when it actually didn’t, or vice versa. We also need to compare the observations with competing hypotheses to show that our hypothesis really is better than others, and not just equally good. If we are sloppy when coming up with hypotheses we might settle for the first thing we think of, when in truth there may be several possible hypotheses, and by spending more time thinking of alternatives we can better evaluate which hypothesis is the correct one. If we are sloppy when making our predictions then we might not be detailed enough in order to really be able to evaluate which of several hypotheses is the correct one. Or we might not think carefully enough about what would be the best way to actually test the different hypotheses. And lastly, if we are sloppy when performing the action that is supposed to test our hypothesis, then we might not do exactly what we thought, or were supposed, to be doing, and so the observations we make are not actually the result of the action we thought they were.

With the help of others

If we want to be efficient in our search for knowledge we would do well to use the help of others. If we had to make all the observations ourselves, compare all observations to all the predictions, come up with all the hypotheses, make all the predictions and perform all the actions, then we would have to live for thousands of years in order to acquire the knowledge of a 10 year old in today’s society. Luckily we can take part of observations, comparisons, hypotheses, predictions and actions that others have done, e.g. by reading a book or talking to a friend. For example, if we have made some observations, we can tell others about them, and they can in turn come up with hypotheses and predictions that we then can use to make more observations in order to figure out which hypothesis is correct. Or we can come up with a hypothesis for observations that somebody else has made, and then tell that person about the hypothesis so that they can use it for their further exploration and come back with the results. It is only because people throughout history have shared their observations, hypotheses and predictions that our knowledge has expanded over the years.

Applying the knowledge method to finding wisdom

Now that we have established the more general method for finding knowledge, we can apply this to the task of finding wisdom. Wisdom is having (the best possible) knowledge of the current situation, goal situation, actions, values and of how the world works. This means that we can use the knowledge method to get better knowledge of our current situations, our goal situations, our actions, values and of how the world works. By collaborating with, or learning from others, we can maximize our chances of gaining the relevant knowledge.

In our first principle analysis of wisdom, we also concluded that our knowledge must hold true over as many different situations as possible, and over as long a time as possible. This means that when we formulate hypotheses to gain knowledge of the world, they should be as general as possible. If we only formulate hypotheses like “in this room on wednesday mornings, when I have just brushed my teeth, if I eat an orange, it will taste weird in my mouth”, then the knowledge we have gained is not very useful. We can be quite sure that it is true, but it applies only to very few situations. Instead we want to make a bolder statement like “everytime that I have brushed my teeth, it will taste weird in my mouth if I eat a citrus fruit in any form”. The advantage of formulating more general hypotheses like that is that if they turn out to be accurate, then we will have gained a lot more knowledge about the world. We can apply the knowledge in many more situations, and thus it will be easier to know how to act in our lives as we come across new situations.

Thus, in order to acquire wisdom, we should try to find as general truths as possible. First principles are the most general truths, and so if we try to make our hypotheses as general as possible, we increase the chances of finding the first principles of a topic.

Now that we have established how to find wisdom from first principles, we can look at how to best teach the wisdom we discover.

Next: Teaching wisdom

Page-ID: 20

This page is version 1.0. It has not yet been reviewed by the global community. Do you want to help improve it? Please leave a comment in the google document for this page, or join the email group to be part of the discussion. You can always share your thoughts via email directly to mail@awiserworld.net. Read more about how you can support A Wiser World.